What’s inside?

It is, according to industry bible, TradeWinds, shipping’s “Huawei” moment – the point when one of the biggest names in the business falls foul of U.S. sanctions, sending shockwaves across the world’s trading and shipping companies.

This latest action – against subsidiaries of Chinese shipping giant COSCO – is the first of its kind, and a big leap from the enforcement actions previously taken against small, shadowy networks associated with Iran, Venezuela, Syria or North Korea.

That’s the headline. But this isn’t a story about COSCO. More than anything, it’s about how simple it has become for a company – even a gargantuan one – to get entangled with the trade in sanctioned oil.

Good Ol’ Days of Sanctioned Shipping

If we look back just a few years, and the trade in Iranian, North Korean or Venezuelan oil, it was heavily reliant on the use of national fleets, such as the National Iranian Tanker Company (NITC) or Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). These operations assumed long-term contracts for supply, with the same tanker carrying the cargo from origin to destination. These are simple, efficient and consistent operations, but also vulnerable when it comes to sanctions because these tankers are easily monitored and punished.

For example, back in 2013, as P&I clubs withdrew their coverage of the NITC fleet, Iran immediately faced a problem of providing the insurance coverage that would enable them to continue entering ports and trading.

Evolving Sanctions Evasion Tactics

This is no longer the case. Sanctions evaders have developed new, more durable, ways to trade under the radar. These include:

- Using multiple different fleets and networks to lower reliance on a single operation

- Removing direct ownership ties to sanctioned entities or countries.

- Making the cargo switch hands at least once during a trade.

- Routinely moving between identities and companies

- Using floating storage in remote locations to disguise the cargo’s origin.

- Letting the passage of time disguise the origin.

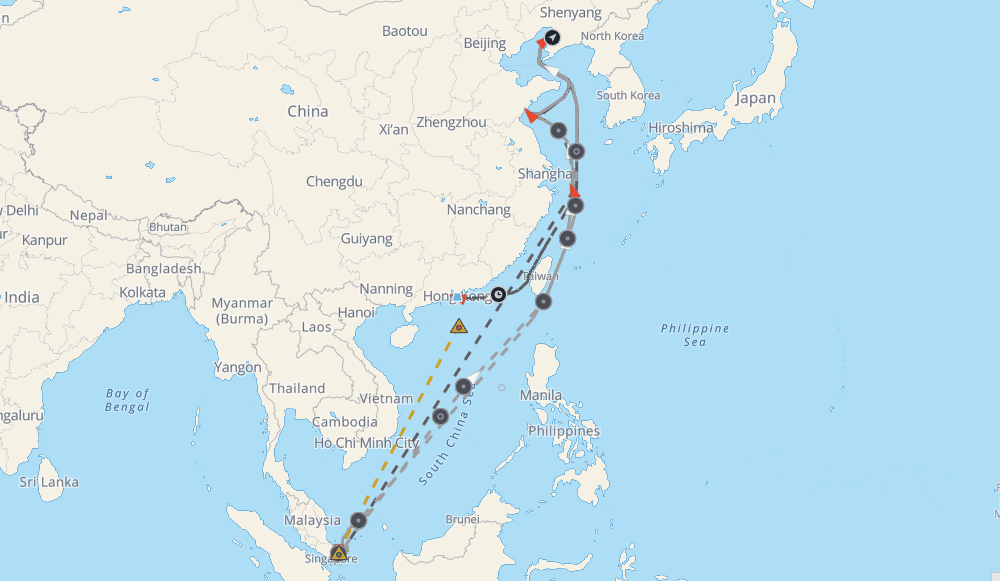

Take the specific operation which actually sparked the recent sanctioning of the Chinese companies. Analyzing the behaviors of the combined fleets related to these companies shows a clear pattern involving a dozen tankers, most of them associated with Kunlun Shipping Co. – and not for the first time.

Generally, this operation has three parts, each crucial to maintain its resilience:

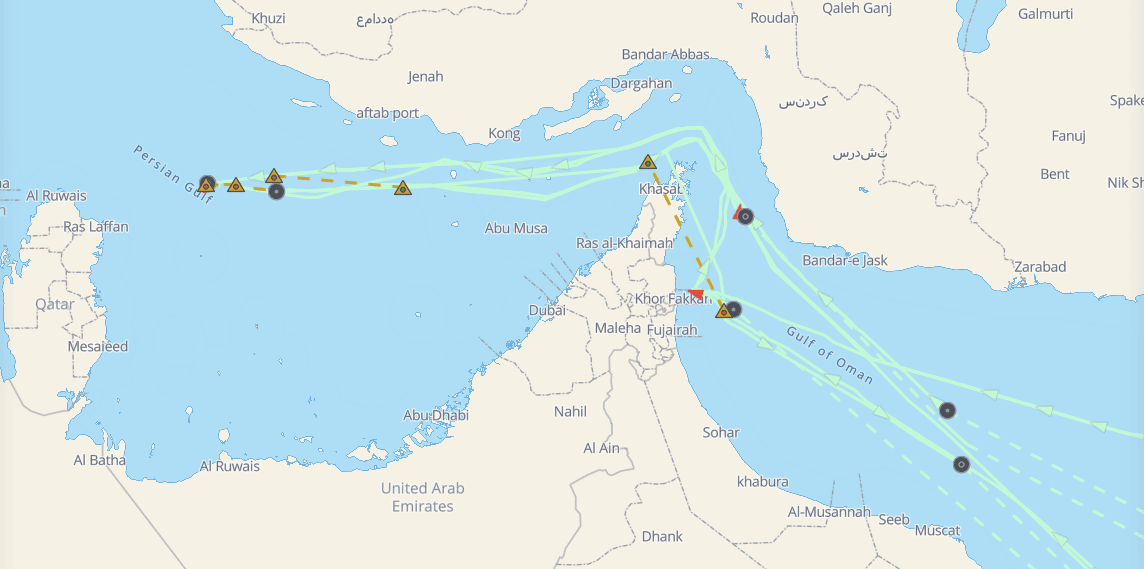

1. Unknown Origin

The Gulf region has become notorious over the past year for vessels turning off AIS transmissions to avoid detection. This simple step is quite effective in raising doubts regarding the real origin of a cargo, as a lack of data on visits to ports is much harder to screen against – if your search for ‘port visits in Iran’, every single one of these sanctions evaders will pass. This operation is designed to exploit this weakness consistently – every voyage to the Gulf would report a false destination, accompanied by several days’ going off the grid.

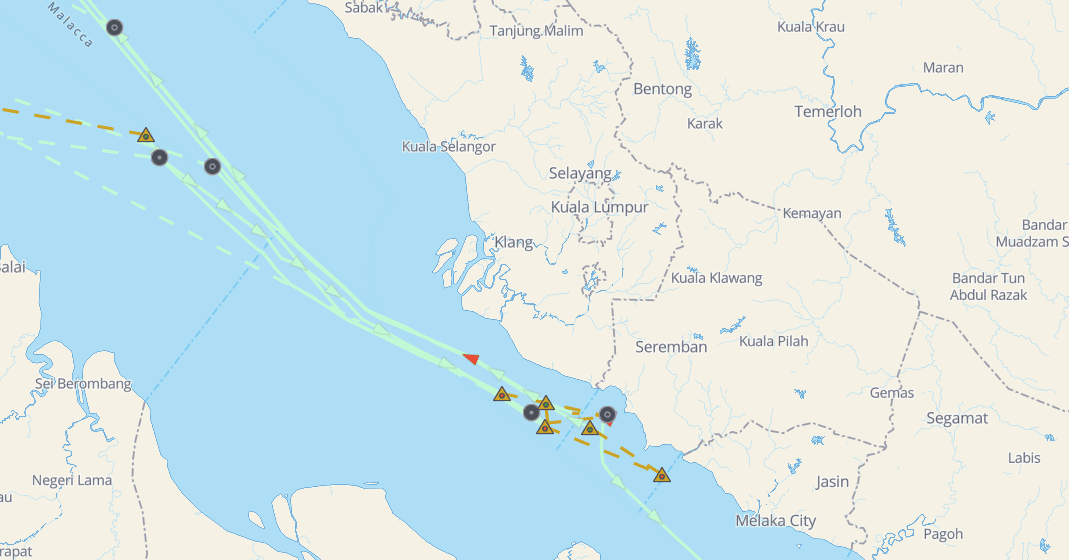

2. Indirect Transhipments

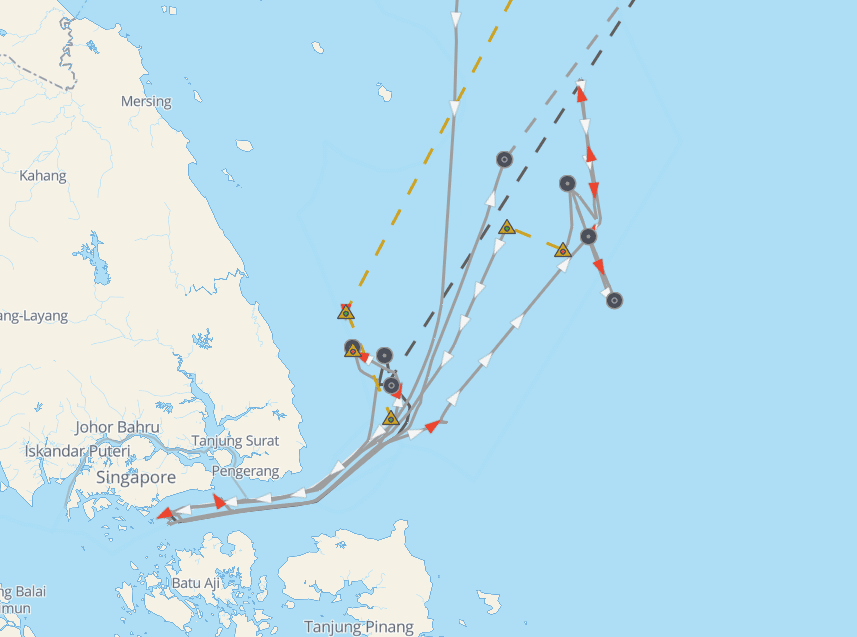

At the heart of this operation is a group of several tankers operating in Malaysia as floating storage, or semi-floating storage, picking up cargo while dark, storing and transporting it for a while, and then delivering it to a third party.

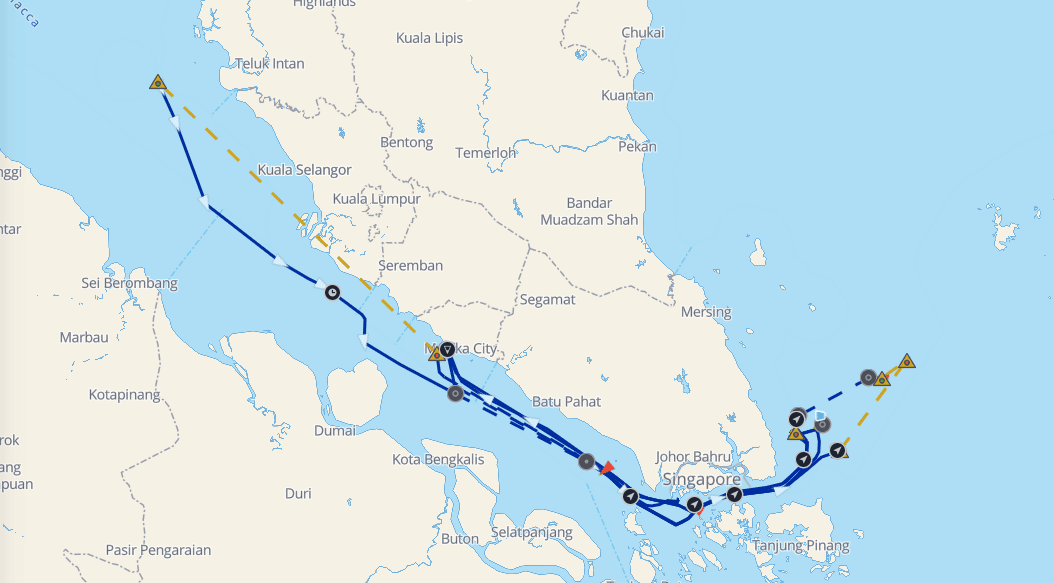

3. Third-party Unloading

Finally, another tanker picks up the cargo in Malaysia, and carries it to China.

This is but one ‘oil laundering’ operation, whose epicenter isn’t even in Iran; rather, it’s in Malaysia, strategically located halfway between Iran and China. Since the designation, we’ve already seen several of these vessels switching ownership and management, moving to new boilerplate, one-ship companies.

To be fair to COSCO Shipping Tanker Dalian, its role in this trade was quite limited. Based on the analysis it wasn’t part of the core operation – it was, it seems, unwittingly sucked into one of these networks. But as we now know (if we didn’t already) ignorance of who you’re trading with doesn’t wash with OFAC – even if it can’t sanction everyone. And of course if COSCO can find itself caught up in a sanctions-evasion ring, many other players in the maritime ecosystem will be wondering who it’s now safe to do business with.